It's May, Bealtaine. The hawthorn's in bloom and nine straight days of sun. I'm standing before my cottage in the pink plumed light that seems to glow. Today, for the first time, I'm looking, really looking, at the stones that form the walls of my shelter. I'm trying to read the layers of time shrouded in whitewash. Trying to imagine the picking and hauling and laying of these stones. Trying to imagine a time before my time, when a house and everything in it was made by one's own hands and the hands of one's near neighbours. A time when a house was made of local, earth materials.

A shock. I realize no money would have changed hands. No shop, no bank, no contractor would have been involved. Every element of the house would have come from the ground transmuted by human hands, including the roof, which is not very high. The roof over one's head here is not that far from the ground. The new slates are fresh and secure, and I try to imagine the former thatch, woven perhaps of the abundance of rushes, and then I see the chimney and the little skein of smoke puffing into the rose-gold sky with its promise of warmth for the night ahead.

On the phone last night my father said he doesn't know what to tell people when they ask why I moved to Ireland. He waited for my answer. I hemmed. I hawed. I didn't have one, a succinct one, a reasonable one. He said he hopes I come home soon. After we hung up, I realized I don't want to go back. This is the place my body wants to be, my soul. Despite the lonely nights, the damp, I feel some inner harmony I've never felt before. I'm no longer out of place in my place. The ground I stand on feels deep. It feels like home land. Or I don't dare to call it home. I barely know what that word means. But maybe that's the word for what I'm feeling. The way every part of me feels right, feels a natural affection for what I encounter. I look up at the sky here and I feel grounded. The clouds are not high and impersonal. They're low to the land, you can nearly touch them. They're local clouds.

But how to explain this to my father? Just before he hung up, this 82-year old man who has never travelled outside the US, told me he's applied for a passport. If I don't come home soon, he warns, he'll come to Ireland, to see what I see.

One answer I could have given my father, and one he may or may not have understood, is beauty. It's beauty that's got me and wants to keep me here. It's not the beauty you drive or hike to because you are separated from it. It's the every-day beauty all around you, inside the house and out. Inside the house it's the beauty of the hand-wrought, the irregular, the non-synthetic, it's the heft and texture of necessity, the absence of excess.

I gaze out the kitchen window, not the window that looks toward the mountain but the window to the back. There's ram. Ram has moved into my garden. He's adopted me. I think he's my angel or my guard. He's not my pet. He belongs to himself. His magnificent black face, his horns upcurled at the sides of his head, his flounce of thick white wool, which every now and then he stands up and shakes out. He rests there, now, on his couch of grass under the ash tree. He gazes back at me with his amber eyes. He knows me, he accepts me. When I go outside to hang the wash or get the turf, he doesn't scurry away. He's dignified. He's beautiful.

The beauty here is like ram, it's wayward and free. It takes its time, enjoys its ease. My beauty is not just the views–misted slope of mountain, rose gold sky–it's my total reality. It's what, I imagine, all the world was before it was reconfigured by the logic of instrumental reason. When land was land. When land was the earth we dwelled upon.

I don't hear many Irish people comment on the beauty. Never have I heard my neighbours say, Oh, isn't that beautiful, will you look at that view? At first I wondered if they noticed it. But now I think that's like asking if fish notice the water.

That it was, in part, impoverishment and famine and poor soil that have left this land so little spoiled adds deeper poignancy to the beauty and its layers of stories. My ear leans toward the voices of this land, toward the cottage ruins, the spilled stones. Perhaps it's the past the local people see and hear when they look out on this beauty. Perhaps what I see as untrammelled, they see as aftermath.

The twelfth century abbot and herbalist Hildegaard de Bingen created a word, viriditas, to describe the healing force of the green world, which is the plant world. Well, the plant world is our world, or was our world. And before the male gods ascended, the green goddess ruled the earth in all her wild splendour and terror. James Hillman has written of the suppression of beauty and, here, in this wild part of the country, I'm experiencing, perhaps for the first time in my life, unsuppressed beauty, viriditas.

In Minnesota I lived in a city that is, like most cities, surrounded by radiating rings of junkspace. Junkspace is another created word, in this case by Dutch architect Rem Koolhass, to describe the proliferating chaos left on the land by consumerism. I suppose all these centuries later, the word junkspace had to be created to describe the ruins of viriditas.

Where I'm from, one can still find remnants of the green world, bits of woodland and meadow, but one must drive through miles of branded, billboarded junkspace to reach them. And so, day-to-day we must live with snatches of remembered beauty, or deferred beauty, and always defaced beauty.

But the old Lakota was wise. He knew that man's heart, away from nature, becomes hard; he knew that lack of respect for growing, living things soon led to lack of respect for humans. So he kept his children close to nature's softening influence.28

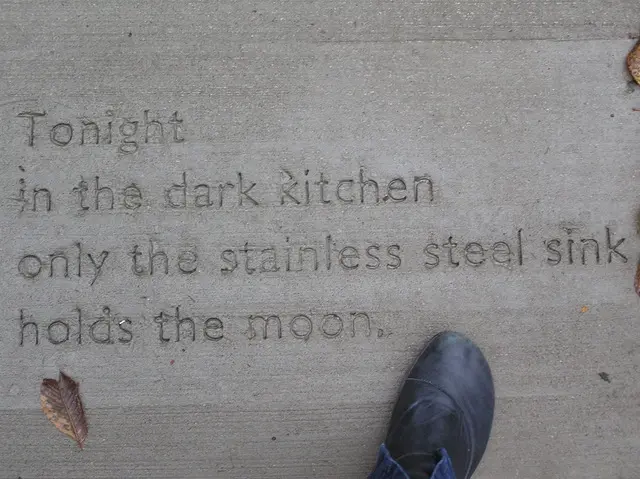

Here, beauty has its way with me. I'm no longer a visitor or onlooker. I'm resident in this beauty. I have an address, a library card, a health insurance policy in this beauty. I have a mop and pail, and pots and pans in this beauty. I hang my wash, gather sticks, and write in this beauty.

Sometimes it's a cold dark beauty that seeps through the stones of the cottage. Sometimes mist and fog beauty, rainbow beauty, bog, endless bog beauty. No, it's not picture postcard beauty up here on the mountain.

Beauty, I'm coming to understand, is not an exterior quality. It's not a quality at all. Beauty is the expression of life. Where there's beauty there's life. And I wonder, is our current artistic and literary obsession with the ugly and depraved a way we rationalize and normalize, or deny and deflect, our destruction of beauty, our culture's destruction of life?

Anais Nin wrote that the nature and appreciation of beauty is an expression of our "need to be in love with the world". She said that the "cult of ugliness is a regression. It destroys our appetite, our love for our world."29 How handy for the developers and miners and oilmen that many of the guardians of our culture, our artists and writers, have for much of the past one hundred or so years turned their backs on beauty. John Berger would say the appreciation of beauty is a vertical activity. Beauty is something you look out and up toward.30 We modernists can only look down or sideways. I'm glad I'm here, with a mountain to look up to.